Nothing incited 16th century Spanish exploration in the new world more than the possibility of finding cities of gold available for plunder. Columbus sailed west to reach the riches of the Far East. Later explorers, each trying to outdo Columbus in finding new worlds, measured their success by the weight of gold booty brought back to delight their monarchs.

Hernán Cortez expanded the domain of Spain in the New World when he dismantled the Aztec civilization of Mexico for the gold objects of great beauty. Francisco Pizarro established a second Spanish New World domain in Peru, when he plundered the Inca treasure of Peruvian gold. There was a belief among Spanish explorers that a third New World empire of gold awaited the diligent explorer. The city was believed to exist in present day Venezuela or Colombia.

Gold-seeking explorers came to the New World in two waves. The first contingent arrived in the mid-to-late sixteenth century, drawn by rumors of an “El Dorado.” A second wave gave new life to the legend of the El Dorado two hundred years later.

Early Seekers of El Dorado

The Spanish dream of an El Dorado grew from rumors of an ancient Muisca tribal ceremony somewhere at a lake in what is now Colombia. In fact, Colombian cultural history includes a leadership induction ceremony that culminates with the new king being bathed in a sticky substance, rolled in gold powder, and thus adorned as a glowing figure head, the king makes a ritual dive into a sacred lake. His followers wish him well and show their homage to the gods by throwing jewels into the lake during the royal washing.

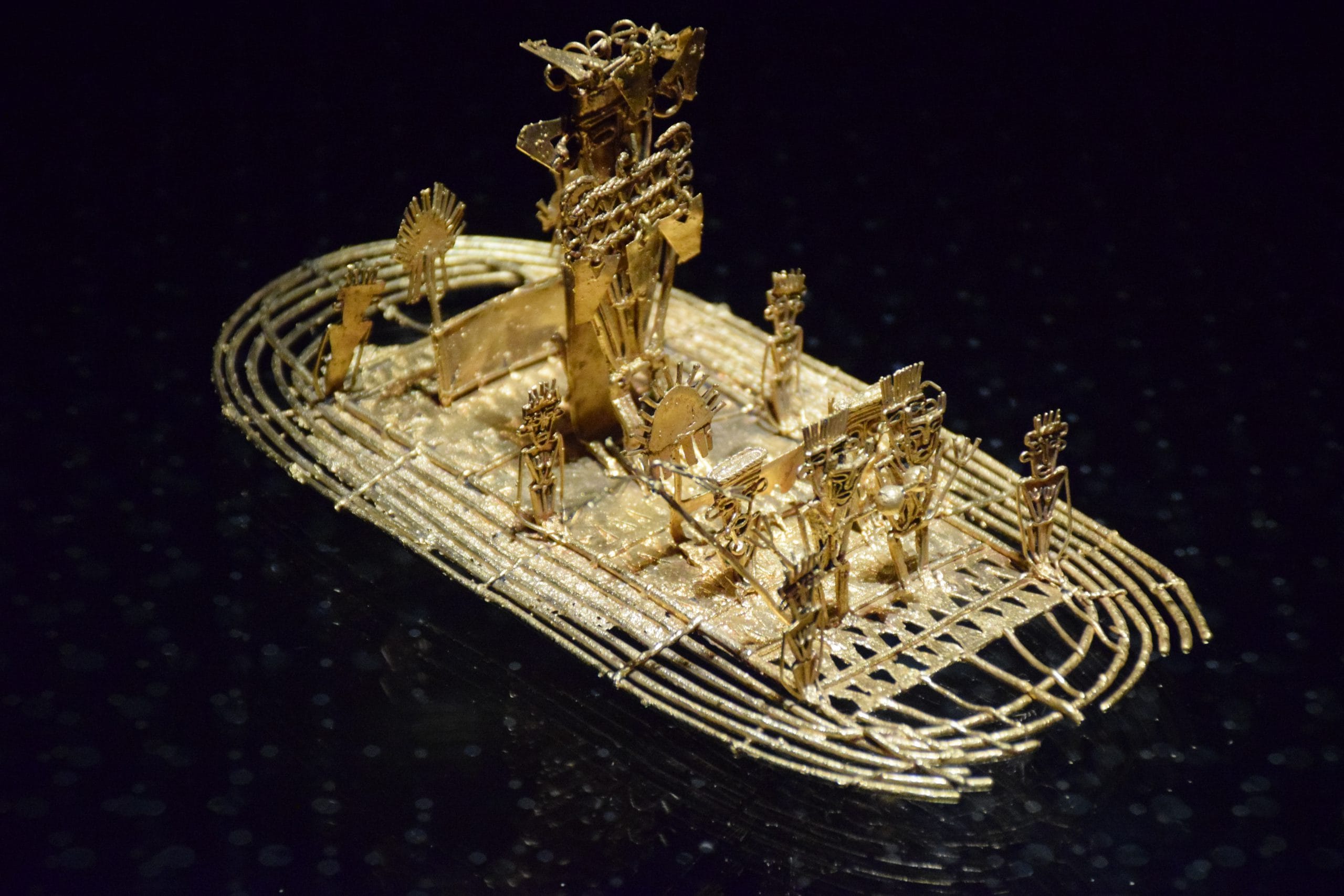

The Muisca people of the gold ritual migrated to parts of Colombia as early as 1270 BCE. Their civilization grew to its high period from 800 to 500 BCE. In the Muisca cosmology, gold represented energy. When not bathed in gold, the Muisca kings sent gifts on a raft to the goddess of the lake.

The Muisca people settled in an area covering from the north of Bogotá to south of the present day capital city of Colombia. Lake Guatavita, an hour north of Bogatá, is thought to be the sacred lake, or at least one of the sacred lakes of the Muisca.

The ritual practice of the Muisca became the source of the legend of El Dorado. It is not known whether the Musica possessed more gold than that used in the ceremony. Regardless, when early Spanish explorers learned of the legend, they acted in full force.

The goal of Spanish explorers was to find the ancient cities of the Muisca, preferably filled with gold, then to retrieve the gifts from the lake. The quest was a worthy calling, even if it monopolized a lifetime and cost a personal fortune. The legend of El Dorado was an all-consuming dream of amazing wealth and fame.

Spaniard Juan Martinez raised the legend of El Dorado to the attention of Spanish explorers when in 1531 he claimed that he was rescued from a shipwreck, taken inland to the lost city of gold, and returned to Spain to raise funds for a recovery party. The Martinez story was similar to an older story repeated around the docks about a wanderer, Juan Martin Albjar, a veteran of the Cortez expeditions. Albjar claimed to have been lost in the jungle for 16 years. He swore that he had seen the lost cities of gold, retrieved souvenirs as proof, and that his gold was stolen from him on his return to the coast, where he was fortunate to find Spanish ships. Over time the tales of Juan Martin and Juan Martinez were embellished to the point of being irresistible.

Inspired by Martinez, Francisco Orellana left the coast of Quito in 1541, in search of El Dorado. His travels took him across the Amazon Basin. Orellana never found his golden goal. Neither did Gonzalo Pizarro, brother to the conqueror of the Inca, find a city of gold on his trek, also through Colombia in 1541.

There were German explorers who searched for El Dorado. Germans Nikolaus Federmann arrived in the 1530s and Phillip Von Hutten came in 1541. They succeeded only in proving that the mythology was accepted as fact in Europe.

The Spanish Quesada brothers Gonzolo Jimenez and Hernán Pérez organized a search of the Orinoco River basin of Venezuela in 1537, with an army of 800 men, and then again in 1540, with 270 men. They encountered natives wearing gold. They followed the natives across the jungles in hopes of finding the source city. Either the city did not exist or the natives were too clever to allow the conquistadors to discover their home. Both efforts ended in failure.

In 1545 Gonzolo Quesada arrived at Guatavita Lake in Colombia, thought to be the sacred lake of the gold king. He ordered his army to drain the lake using buckets. After draining Gonzolo and his financiers of their resources, about 3,000 pesos worth of gold were recovered from the lake, worth about $100,000 today. Gonzolo died believing that he had succeeded in his quest.

In 1580 Antonio de Sepúlveda arrived at Gonzolo’s drainage site. He cut a channel around the lake to allow the water level to fall. About 12,000 pesos of gold were recovered before the channel collapsed and several of the workers were killed. Sepúlveda died while trying to find more gold.

Antonio de Berrio also joined the list of conquistadors attempting to locate the city of the El Dorado in 1580. Berrio was sixty years old at the outset of his quest. He was a seasoned soldier, having led battles for Spain at Lepanto and in Germany, Sienna, and Granada. The old soldier would have been pleased to retire on the estate of his wife’s uncle who was the Spanish governor of Trinidad. The uncle, who was one of the Quesada brothers, bequeathed to Berrio the governorship and the quest for El Dorado.

Over the next sixteen years Berrio trekked across present day Venezuela and Colombia. He led three lengthy expeditions in 1584, 1585, and 1591. A few members of the expeditions with independent means organized their own search, hoping for instant fame.

By 1594 the news from Trinidad was so enticing that British opportunist Sir Walter Raleigh decided to mount his own search team, ostensibly on behalf of Britain and Queen Elizabeth I. He made the argument that there must be a city of gold or there would not have been so many Spaniards involved for so long, and at such great cost. Raleigh found no gold and headed instead to Virginia, but not before he laid waste to the home of Berrio in Trinidad.

Raleigh arrived in Port of Spain, Trinidad under a flag of peace. He invited Berrio onto his ship, with others who were questioned for knowledge of El Dorado. When Raleigh’s guests were safely under the influence of wine, his men stabbed them. Berrio was held prisoner. Raleigh’s men looted and set fire to the Spanish settlement at Port of Spain. Two centuries later, the liberator of South America, Simón de Bolivar, commented on the 1595 English raid on Port of Spain, praying to god that the legend of El Dorado cease to exist.

Years later Raleigh returned to Trinidad where he incited a battle that cost the life of Walter, his son. At this time the English were negotiating an end to hostilities with the Spanish. Raleigh’s actions ran counter to diplomatic efforts. His enemies at court unleashed years of pent-up resentment of Raleigh. He was executed in London in November 1618, ending the first wave of English and Spanish dreams of finding El Dorado.

The Second Wave and Futile Reclamation Projects

At the beginning and end of the nineteenth century there was renewed interest in the search for El Dorado. From 1799 to 1804, Alexander Humbolt led an expedition to Lake Guatavita. Initially, Humbolt relied upon the sixteenth century experience of Antonio de Sepúlveda to proclaim that 300 million pesos in gold lay in the lake. By the time Humbolt ran out of funds and patience, he was ready to announce that the legend of the El Dorado was merely a myth.

The failure of Humbolt’s efforts had no effect on the group of men, who in 1898 formed the Company for Exploitation of Guatavita. The British employed modern reclamation technology to achieve that which those before them could not. The company was successful in draining the lake. They achieved a pond that was four feet deep in mud. When the mud dried it hardened to the consistency of cement. Only £500 in gold was recovered from the lake before further recovery became impossible. The company quickly went bankrupt. It ceased operation in 1929.

The Colombian government is open to foreign visitors. It is, however, concerned about devastation to the environment by the actions of foreign corporations. In 1965, Lake Guatavita became a government-protected area. Scars of drainage efforts can still be seen in the side of the lake wall. The area has been protected from further reclamation efforts. The lake trail is a great day hike for visitors.

The legend of El Dorado that began with actual ceremonies of indigenous people, ended with the knowledge that these early residents held sacred a rare commodity. There never was a third gold dominion for the Spanish to conquer. The searches only resulted in an accelerated end to seekers of quick wealth. The lessons endure.

For a guided tour to Lake Guatavita, an hour north of Bogotá, contact DestinoBogota.com. A 9th century, 19 inch, gold replica of a Muisca ceremonial raft is in the Bogotá Gold Museum. The raft was found in a cave south of the city.

For more on this story and others in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, see Cruise through History, Itinerary VIII, available at Amazon.com.